In medical school, I learned a five step model on how to deliver bad news to a patient. I still fall back on this method, time and again, in my primary care clinic; I’ve even used it when giving really tough feedback to a learner who is struggling in some aspect of their performance. But I honestly never thought I would be applying these steps to my own children—breaking the news that mom has breast cancer.

In 2016, as a practicing internist, I found a lump at home, while doing a breast self-exam in the shower. I knew something wasn’t quite right; I wasn’t all that surprised when the mammogram showed a suspicious finding. My first one, actually, at 44–I hadn’t started screening yet, uncertain of the evidence to support it. But now, it’s been one week since the biopsy returned positive for cancer; I’ve had appointments with Surgery and Oncology, I am starting to get a better sense of the plan. It seems like now is the time to let my children in on the situation, but naturally, I am feeling nervous.

I sought advice from several friends who were physicians and also parents themselves; I did get some helpful suggestions. “Tell them just enough information, and not too much; let them ask the questions, I’m sure they will surprise you.” My radiology colleague who was diagnosed with metastatic colon cancer at age 50 told me to involve their teachers at school, and to be blunt, honest, and direct. Her kids were older, though, teenagers; what about Sam and Lydia, at the tender ages of 8 and 11? After talking it over with my husband, an architect, he thought I should lead the discussion, and maybe appropriately so; we both reasoned I had the background medical knowledge and also the training in this particular skill set which would hopefully come in handy.

The opportunity to have “the talk” arose on a Thursday evening, right after parent teacher conferences. As part of Sam’s 5th grade conference, he was given an assignment to write about what he is learning, what he enjoys most, and goals for the next quarter. I had just seen this document; it was meant to frame the discussion for those 15 minutes with his teacher. On this, he had written “The Cell” as one of his most enjoyable learning topics. Aha, a good way to open the conversation. I called them both into the kitchen; I am sure they thought this was going to be some sort of debrief about report cards.

I am standing at the counter fixing dinner and I say, “So, parent teacher conferences went well!” I am trying to act casual, as I am peeling raw shrimp for use in a pasta. Their flimsy crustacean shells and odd shaped legs fling down into the metal colander as I work, while Sam and Lydia are sitting at the kitchen table. I turn to Sam and ask, “What do you know about the cell?”

“Well, you know, the cell is the building block of the human body. Every part of us is made up of cells.” Indeed, I say, how fascinating. “What do you know about cancer?” I ask. (Find out what they know.) Sam says, “Cancer is when cells grow out of control and like, take over your body and spread and stuff.” Very good, I think. Our education dollars are going somewhere.

“Well, along those lines, I am afraid that your Mom has something to tell you.” (Warning shot.) “I found a lump in my breast, my doctors did a biopsy and discovered it is cancer.”

I pause, swallow hard. I had tried not to mince words, but maybe this was too much; I will never forget the looks on their faces. Sam, sitting silent, and his pale blue eyes with their long sandy blond lashes simply widened. Visibly widened, and he just froze, staring back at me. Then Lydia, with her beautiful hazel eyes and dark lashes, they just turned red and immediately filled with tears.

I go on to say, I know this sounds frightening, but I am quite fortunate, I found this lump early. I’m seeking care at the University, to have the best physicians on board, the A team. I will have surgery to remove it, followed by medicine to control it. And I feel fine! This is the best possible scenario! It’s a very treatable disease, I say. (Share information).

At which point Sam asks, “But is it curable?” Darn it, too smart for his own good. I answer yes, it is potentially curable. “But could it come back?” Wow. Well, I say, that is a very good question; in theory it could come back, but the medicine prevents that from happening. Lydia is still shedding tears and asking if my arms and legs feel weak from cancer. I tell her no, I am still running, I can still go on bike rides with her. Sam says, “Well at least you are able to keep doing what you want to do.” What is this, a future oncologist commenting on functional status? I cannot believe I am hearing these responses.

We exchange hugs, talk a bit more; I tell them it’s perfectly normal to feel sad or scared, and of course I do too, but I have complete trust in my team of doctors. (Respond to their feelings). Eventually we sit down to eat; I mention over dinner, if it helps, they can tell their close friends, and I will speak with their parents, or talk to their teachers if they would like them to know. (Plan the follow through). Later, before bed, we all pray together about it.

But over the coming days, Sam pretty much clams up about the topic; he doesn’t mention it, doesn’t tell his friends, doesn’t want me to talk with his teacher, Mrs. Horn. Lydia, on the other hand, tells her two best friends and they tell two friends and so on. She informs not only her current third grade teacher but her beloved second grade teacher as well. She’s a very artsy, creative girl, loves to draw; she and her classmates design a colorful “get well” card for me at school. Later, I did find out Sam was keeping a journal and wrote a few entries regarding the cancer diagnosis; this I was glad to hear, writing can be extremely therapeutic. It was interesting and a bit heartwarming to see how each of them processed the information; neither being better or worse, just different.

In fact, after the initial panic, Lydia shifts gears, and later becomes almost my home visiting nurse. Every day, wants to know how I am feeling, is there any pain, have I eaten enough today, have I gotten any exercise, when are my other tests coming back. Along a similar vein, she actually wants to feel my lump. I am really conflicted about that–what should I do? Am I going to warp an 8 year old girl for the rest of her life? This is pretty scary stuff.

Eventually I decide, well, why not. It might help to have some sort of tangible explanation of what is going on. She presses in where I had originally felt it; it’s quite superficial, at “1 o’clock” as they say, just above my bra line, fairly obvious. After the biopsy, there was a bit of swelling, now it seems bigger than when I originally discovered it (or is that my imagination?) She does feel it, right away, and makes a perfect face: a cross between a frown and an expression of disgust, best described simply as “eeeww.”

I couldn’t agree more. I tell her, it’s yucky, it’s gross, now let’s get rid of it. On Tuesday, April 26, to be more precise.

On that day, before leaving the house, I explain to Sam and Lydia that it should be a same day operation, unless something unexpected happens; I wanted to prepare them, just in case I ended up admitted to the hospital. But surgery went very smoothly, and when I walked through the front door later that afternoon, that was yet another look on their faces I will never forget. Sitting on the couch with our nanny, they leapt to their feet, wearing an expression of sheer joy, happiness, relief; even surprise that I felt pretty good, had minimal pain. And during recovery, Lydia became my home visiting nurse, once again. Wanted to look at the incision, check the drain output, assist with the dressing changes. I couldn’t help but wonder if these experiences would have any influence in terms of a potential career path down the road.

In the coming weeks, more questions. Tucking Lydia in for the night, sitting on the edge of her bed, between a menagerie of stuffed animals and a pile of books, suddenly she asks, “What if I get breast cancer? And what if it’s not stage 1, but stage 4?” After I swallow hard and take a deep breath, I think, wow, children overhear more conversations around this house than I think they do. My 8 year old is asking about cancer staging, for God’s sake!

“Well,” I say, not really sure how to answer. “Just to be certain, you will have X-rays, to look for this ahead of time.” By my calculation, she should start at age 34. “You mean an MRI? I don’t want to have an MRI!” she says. Whoa. Again, those big ears, overhearing me describe how loud and confining the machine felt. “Well, yes, maybe an MRI. Or by then, some newfangled high tech total body scan that can evaluate for any cancer, anywhere in the body!” For a moment, the physician in me took over; I went on to discuss how many advances have been made in the earlier diagnosis and treatment of many types of cancer, breast cancer included. I was also, by this point, able to reassure her about my negative genetic testing. Relaying this did seem to visibly calm her, but once again, I thought of the 5 steps, and I am reminded: Respond to their feelings. I shift the conversation towards that, instead, validating her concerns, the fear, the anxiety surrounding my diagnosis. I share with her how I’ve been coping with it, myself; music, writing, exercise.

Many months later, approaching my 12 month follow up, we would talk about the significance of that date—one year cancer free—and Lydia even coins a new term for it: “cancer-versary.” It has turned into something we want to celebrate, now, as a family, instead of fear or dread. Sam even let me read the journal entry he wrote one year ago, on that date, April 26th. In typical teenage boy fashion, it was brief, direct, and to the point. “4/26/16. (Log). Tuesday. Today I practiced my play instead of having English class. And…my Mom is cured of cancer! Today was good.”

Indeed. In retrospect, I can say, that day was good. Reading those simple yet profound words I was reminded of the poet’s phrase: Hope springs eternal in the human breast. Yes, even in the hearts and minds of young children. I will keep this important point in mind, the next time I am called upon to deliver bad news to a patient. There might be an additional element in breaking bad news: hope, hopefulness, the need to share something positive. Because even the darkest situations can have an element of hope; there is always “something we can do,” even if it extends life but does not cure, or simply helps relieve pain and suffering.

Over four years out, I was once again reminded of the complexity of breaking bad news to children. Seeing one of my long time patients in clinic, I notice he is visibly stressed; he then relays to me that his wife was just diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer despite never having smoked a day in her life. After further discussion, expressing empathy, and more therapeutic listening, he suddenly asks: how do we tell the kids?

After I pause, swallow hard, and ponder—how much should I share?—I mention several resources, including some helpful websites and two books written on the subject. And after leaving the exam room, I reflect on my own struggles. Looking back, that was possibly the most difficult “bad news” I had to deliver, considering the emotional impact on those I love. But it also taught me the importance of involving family in the conversations early on, even young children; it also reminded me how intuitive and resilient children can be.

After contemplating a bit more, wrestling with it, I decide I want to use this experience to benefit my patients, other moms and dads, and hopefully their children, even if I never get to meet them. I come back to the room with his after visit summary in one hand, and a copy of this essay in the other.

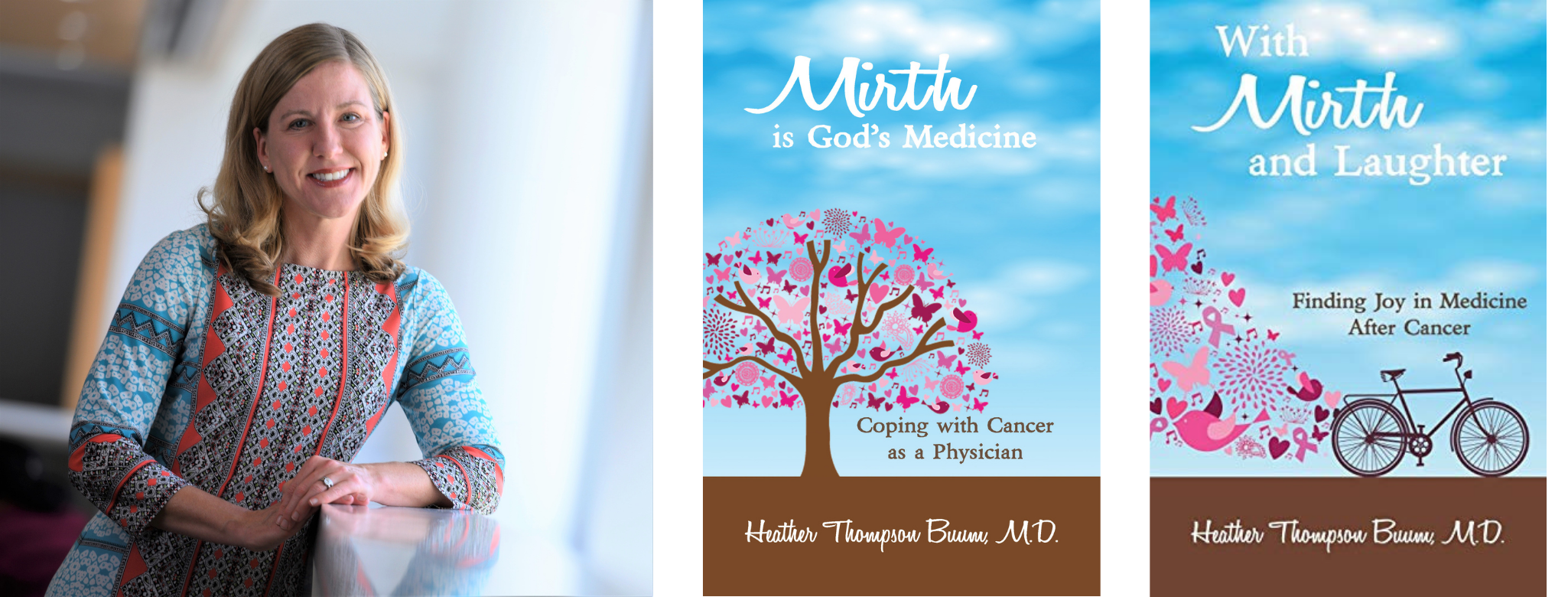

This article was originally published in The Journal Of Clinical Oncology. “Out of the Mouths of Babes: A Physician Discusses Her Cancer Diagnosis With Her Two Young Children.” JCO 2019; 37 (1):81-83.